Historical overview Nigeria's religious landscape, marked by a near-even split between Islam and Christianity alongside resilient traditional beliefs, was shaped by centuries of indigenous practices, trade, and colonial influences. Before the arrival of exogenous faiths, diverse ethnic groups practised animist and ancestral religions, embedding spirituality in social and political life. Islam, introduced through 11th-century trans-Saharan trade, established northern strongholds, while Christianity, arriving with 15th-century Portuguese explorers and expanding under 19th-century British colonialism, took root in the south.: 53–55 These historical layers underpin Nigeria's modern religious diversity and regional polarisation.

Indigenous religions Before Islam and Christianity, Nigeria's ethnic groups, including the Yoruba, Igbo, and Hausa, practised decentralised religions centred on a supreme creator and intermediary spirits. These traditional belief systems were largely oral, with teachings transmitted through folklore, ritual, and communal ceremonies. Religion was not viewed as a separate sphere of life but was deeply embedded in social, legal, and political institutions. Most systems emphasised the worship of a supreme creator god who was often regarded as distant, with intermediary deities, ancestral spirits, and natural forces playing more active roles in daily affairs. These intermediaries were believed to inhabit rivers, trees, hills, and sacred groves, and were honoured through ritual offerings, prayers, and festivals.

Among the Yoruba, religion centred on a structured pantheon of deities known as orisha, each associated with specific domains of life and nature. Prominent orisha included Ogun (god of iron and war), Sango (thunder and justice), and Yemoja (motherhood and the sea). These deities were worshipped in shrines and through elaborate rituals that included music, dance, and sacrifice.: 15–20 In the southeastern region, the Igbo religious worldview revolved around Chukwu, a supreme god who created the world and delegated authority to lesser spiritual beings and ancestral forces. Each individual was believed to possess a personal spirit, or chi, which guided their destiny. Communities maintained sacred groves, personal altars, and cultic practices honouring deities such as Ala (earth goddess), who governed morality and fertility. Priests, diviners (such as the Yoruba babalawo or Igbo dibia), and spiritual leaders played key roles in maintaining the religious order. They conducted rituals, interpreted signs, mediated conflicts, and acted as custodians of sacred knowledge. Religious festivals and ceremonies marked the agricultural calendar, rites of passage, and transitions such as birth, initiation, marriage, and death. These indigenous systems were highly resilient, adapting over time and in many cases persisting even after the spread of Islam and Christianity. Elements of traditional belief continue to influence cultural practices, political structures, and popular spirituality in modern Nigeria.: 53–55

Introduction of Islam Islam first entered the territories of present-day Nigeria through trans-Saharan trade routes in the 11th century, primarily via the Kanem-Bornu Empire in the northeast. This initial contact occurred through interactions with Berber and Arab traders who brought Islamic teachings alongside goods like salt, textiles, and gold. The Kanem-Bornu Empire, centered around Lake Chad, became an early hub of Islamic scholarship, with rulers adopting Islam as early as the 11th century under Mai Umme Jilmi. The religion spread gradually westward into the Hausa states, including Kano, Katsina, and Zaria, which emerged as major Islamic centers by the 14th century.

The spread of Islam was driven by merchants, itinerant scholars (mallams), and clerics who established Qur'anic schools, mosques, and Islamic courts, integrating Islamic practices into local governance and daily life. These scholars often belonged to Sufi brotherhoods, such as the Qadiriyya, which emphasized spiritual discipline and facilitated the religion's appeal among local populations. Trade routes connected northern Nigeria to Islamic centers in North Africa and the Middle East, fostering the exchange of ideas and the adoption of Arabic literacy for religious and administrative purposes. By the 15th century, Islam had become entrenched in the Hausa states, where rulers adopted Islamic titles like sarki and implemented Sharia-based legal systems in urban centers. The religion coexisted with traditional practices, as many communities blended Islamic rituals with indigenous beliefs, such as veneration of local spirits. Islam's influence expanded significantly in the 19th century during the Fulani Jihad, led by Usman dan Fodio, a scholar and reformer who sought to purify Islamic practices and establish a unified Islamic state.: 15–23 The jihad, launched in 1804, resulted in the creation of the Sokoto Caliphate, a major Islamic political and religious entity that unified much of northern Nigeria under a centralized Sharia-based administration. The caliphate's establishment marked a pinnacle of Islamic influence, with its network of emirates promoting Islamic education, law, and culture across the region.

Spread of Christianity Christianity was introduced to the Nigerian coast in the late 15th century by Portuguese explorers, particularly in the kingdoms of Benin and Warri. Catholic missionaries, primarily Augustinians and Capuchins, accompanied these expeditions, establishing small missions and baptising local elites, including members of the Benin royal court. However, these early efforts had limited long-term impact, as the Portuguese prioritized trade in spices, ivory, and enslaved people over sustained missionary work, and local conversions often reverted to traditional practices. Significant Christian missionary activity began in the 19th century during British colonial expansion, facilitated by the abolition of the slave trade and the establishment of coastal settlements.

Missionaries saw the conversion of Africans to Christianity as a means of social reform... The new religion was often presented as a liberating force against both the slave trade and 'superstition'.

Protestant groups, including the Church Missionary Society (CMS), Methodists, and Baptists, focused on southern Nigeria and the Middle Belt, establishing missions in places like Badagry, Lagos, and Abeokuta. The CMS, led by figures like Samuel Ajayi Crowther, a Yoruba ex-slave and ordained minister, played a pivotal role in translating the Bible into Yoruba and training local clergy.: 15–20 Catholic missions, revitalised by the Society of African Missions and Holy Ghost Fathers, expanded in southern and central regions, establishing schools and churches in Onitsha and Calabar. Sierra Leonean returnees, many of whom were freed slaves converted to Christianity in Freetown, played a significant role in spreading the faith, particularly among the Yoruba. These returnees, known as Saro, established Christian communities and schools in Lagos and Abeokuta, blending Western education with evangelical outreach. Missionary schools became key instruments of conversion, teaching literacy, Christian doctrine, and European customs, which often clashed with indigenous practices like polygamy and traditional worship. Despite resistance from local rulers and priests, Christianity gained traction in southern Nigeria, laying the foundation for its later growth.: 15–20

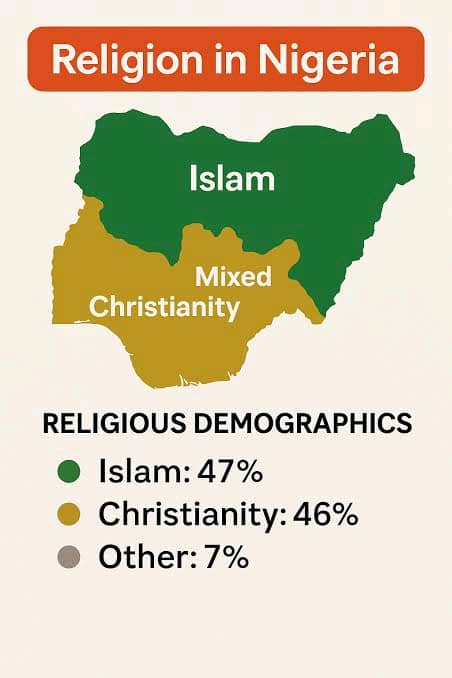

Contemporary religious demographics National overview Nigeria is among the world's most religiously diverse nations, with its population almost evenly divided between Islam and Christianity, alongside a diminishing but culturally significant presence of indigenous and other religious groups. Due to the absence of a national census that includes religious affiliation since 1963, current estimates of Nigeria's religious demographics are based on independent surveys and research studies. These estimates can vary significantly depending on the survey's sample size, methodology, region of focus, and the political or social climate at the time of data collection. As a result, figures from sources such as the Pew Research Center, Afrobarometer, and the CIA World Factbook often differ slightly but consistently reflect a near-even split between Islam and Christianity, with a small percentage adhering to traditional or other beliefs.: 53–55

A 2022 Afrobarometer survey reported 54.2% of Nigerians as Christian, 45.5% as Muslim, and 0.3% adhering to other or no beliefs, possibly reflecting southern Christian-heavy sampling. The Pew Research Centre’s 2010 estimates, based on 2008 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data, showed 49.3% Christian, 48.8% Muslim, and 1.9% indigenous or other religions, indicating a near-even split. Pew’s 2015 estimates, adjusted for higher Muslim fertility rates (7.2 vs. 4.5 for Christians in 2013 DHS) and younger Muslim age structure, reported 50% Muslim, 48.1% Christian, and 1.9% other, suggesting a slight Muslim majority. The CIA World Factbook’s 2018 estimate indicated 53.5% Muslim, 45.9% Christian (10.6% Roman Catholic, 35.3% other Christian), and 0.6% other religions, potentially emphasising northern Muslim-majority regions. Variations across these estimates stem from differences in survey sampling, regional focus, and demographic adjustments, with Pew’s 2010 and 2015 figures reflecting evolving fertility and age trends.: 53–55

Regional and state-level distribution Religious affiliation in Nigeria is deeply shaped by regional, ethnic, and historical factors, resulting in pronounced geographic polarization. Islam dominates the northern states, Christianity prevails in the southern regions, and the Middle Belt serves as a religious crossroads, hosting significant populations of Muslims, Christians, and indigenous believers.: 15–20 A 2012 study by Philip Ostien, which adjusted 1952 and 1963 census data to Nigeria's current 36-state structure, underscored this divide. Northern states like Sokoto, Kano, and Borno had Muslim majorities exceeding 90%, while southern states such as Anambra, Enugu, and Imo had Christian majorities above 90%. Middle Belt states, including Plateau, Benue, and Nasarawa, exhibited more balanced demographics, often with Christian majorities coexisting with sizable Muslim and indigenous communities.: 15–20 The 2022 Afrobarometer survey confirmed this pattern, reporting over 95% Muslim populations in northern states like Jigawa and Zamfara, and over 95% Christian populations in southern states like Rivers and Cross River. The southwest, particularly Lagos and Oyo, is an exception, with roughly equal proportions of Muslims and Christians, reflecting the Yoruba’s pluralistic religious heritage.: 15–20 A 2010 Pew Research Center survey found that among the Yoruba, 55% are Muslim, 35% Christian, and 10% adhere to indigenous or other beliefs, while the Igbo in the southeast are 98% Christian, and the Hausa-Fulani in the north are 95% Muslim. This ethnic-religious alignment is rooted in historical developments: the Hausa-Fulani embraced Islam through the Sokoto Caliphate in the 19th century, while the Igbo adopted Christianity during colonial-era missionary activities.: 15–23 Ethnic affiliations further shape religious patterns. The Hausa-Fulani's Islamic identity is reinforced by cultural institutions like the Sharia-based emirate system, while the Igbo's Christian dominance reflects the influence of early Catholic and Protestant missions in the southeast.: 15–23 The Yoruba's religious diversity, fostered by centuries of trade and cultural exchange, allows for fluid interactions between Islam, Christianity, and traditional practices like Ifá divination.: 15–20 In the Middle Belt, ethnic groups like the Tiv and Idoma often blend Christianity with indigenous beliefs, such as ancestor veneration, while Islam has gained traction in states like Niger and Kwara through historical trade routes.: 15–20

Major religions in contemporary Nigeria Nigeria's religious diversity, rooted in pre-colonial spirituality and shaped by Islamic and Christian influences, features traditional beliefs (1–7%), Islam (45.5–53.5%), and Christianity (45.9–54.2%) as dominant faiths. These religions, reflecting regional patterns—traditional beliefs nationwide, Islam in the north, Christianity in the south—shape modern Nigeria's culture, politics, and social life. This section explores their contemporary practices and societal roles.

Traditional beliefs Traditional beliefs, practised by 2–15 million Nigerians, persist across ethnic groups, often alongside Islam or Christianity, shaping festivals, governance, and identity. Rooted in pre-colonial spirituality, these systems venerate a creator god and spirits, with a resurgence driven by cultural pride.

Southwest and South-South traditions Yoruba religion, centred on Ifá divination and orisha worship, thrives in Oyo and Osun, with global reach via diaspora. The Osun-Osogbo festival, a UNESCO site, draws thousands annually. Edo traditions in Edo State venerate spirits like Olokun, influencing local festivals.

Southeast traditions Igbo religion, focused on Chukwu (supreme god) and ala (earth spirits), persists in Anambra among 0.5–3 million adherents, often syncretised with Christianity. Efik religion in Cross River and Akwa Ibom, with 0.2–0.5 million followers, worships Abasi Ibom and ndem spirits, with festivals like Ababa boosting cultural tourism.

North and Central traditions Abwoi, a male ancestral cult among the Atyap in southern Kaduna, involves secret initiation rites and venerates ancestral spirits, shaping governance and social cohesion for 0.1–0.3 million adherents. It influences male identity and fertility practices, persisting despite Christian and Muslim influence. Hausa animism in Kano, with 0.1–0.5 million practitioners, includes Bori possession rituals, often syncretised with Islam. Tiv traditions in Benue, followed by 0.1–0.3 million, centre on Aondo, guiding social practices. Ibibio religion in Akwa Ibom, with similar numbers, revolves around a supreme god and Ekpe society, influencing festivals.

Islam Islam, dominates northern Nigeria, including states like Kano and Sokoto, and extends to the southwest and Mid-West. Rooted in 11th-century trans-Saharan trade, it shapes education, law, and governance in northern communities, with diverse sects reflecting Nigeria's complex religious landscape.

Sunni and reformist movements Sunni Islam, primarily following the Maliki school with a smaller Shafi’i presence, constitutes the majority of Nigerian Muslims, concentrated in northern states and Yoruba-speaking areas of the southwest. The Jama‘atul Izalatul Bid’ah Wa’ikhamatul Sunnah (Izala), founded in the 1970s, promotes a reformist agenda, emphasising scriptural adherence and influencing urban centres like Kaduna and Jos. Sunni practices, including daily prayers and Ramadan, underpin community life.

Sufi brotherhoods Sufi orders, notably Qadiriyya and Tijaniyya, engage approximately 37% of Nigerian Muslims, fostering mysticism and interfaith tolerance. Prevalent in northern cities like Zaria and Kano, Sufi practices include devotional festivals and shrine veneration, which attract diverse communities. Their emphasis on peaceful coexistence shapes local inter-religious dynamics.

Shia Islam Shia Muslims, estimated at 2–4 million, are concentrated in Sokoto and Zaria, led by the Islamic Movement of Nigeria (IMN), which faced a government ban in 2019 due to clashes with authorities.

Christianity Christianity prevails in southern states like Lagos and Enugu, influencing education and politics. Introduced by 19th-century missionaries, it shapes southern and Middle Belt communities. Protestants add diversity.

Catholicism, Lutheranism and Anglicanism In Nigeria, Catholics number 20–25 million, Lutherans number 2.4 million, and Anglicans number 15–20 million. These Churches dominate in Igboland and Yorubaland, with cathedrals and seminaries as key institutions. Their schools drive education. The two major Lutheran denominations include the Lutheran Church of Christ in Nigeria (LCCN) and the Lutheran Church of Nigeria, with the former having its membership base in the north and the latter having its membership base in the south.

Pentecostal movements Pentecostalism, led by churches like Redeemed Christian Church of God, attracts urban youth via media and mega-churches, with ~30 million adherents.

Indigenous Christian churches Indigenous churches, like Aladura and Celestial Church of Christ, blend African and Christian spiritualities, thriving in Yorubaland with millions of followers.: 15–20 Healing services are central.

Superstitions Superstitions in Nigeria encompass a wide range of cultural beliefs and practices that are deeply embedded in the nation’s social and spiritual life. These beliefs are intricately intertwined with religious practices, influencing traditional African religions, Islam, and Christianity. Beliefs in witchcraft, jinns, and spiritual curses shape behaviours across religious communities, often blending with rituals such as Christian deliverance sessions, Islamic Quranic recitations, or traditional divination practices. They impact health, education, economic activities, and social interactions, forming a significant aspect of Nigerian culture that transcends religious boundaries.

Minority religions Minority religions, encompassing less than 1% of Nigeria's population, contribute to its diverse religious landscape, often in urban centres.

Baháʼí Faith and Hinduism The Baháʼí Faith, with 30,000–50,000 adherents, is active in northern and southern Nigeria, promoting unity and interfaith dialogue through community centres in cities like Abuja. Baháʼí schools and festivals foster education and social cohesion.: 123–125 Hinduism, practised by about 25,000 Nigerians, primarily Indian diaspora in Lagos and Port Harcourt, centres on temple worship and festivals like Diwali.: 123–125 Hindu communities maintain cultural ties through schools and charity.

Judaism A small number of Nigerians, primarily among the Igbo ethnic group, practise Judaism. These communities observe Jewish customs such as circumcision, Sabbath-keeping, dietary laws, and the celebration of Jewish festivals. Some Igbo Jews identify as descendants of the ancient Israelites, specifically the tribe of Gad, though this claim is not recognised by mainstream Jewish authorities. Estimates of Nigeria's Jewish population range from several hundred to over 3,000 individuals. Synagogues exist in cities such as Abuja and Port Harcourt, often supported by international Jewish organisations. These communities, while small, contribute to the country's religious diversity and have drawn international attention.

Syncretic and other movements Syncretic movements, such as Chrislam, which blends Christian and Islamic practices, attract small but growing urban followings in Lagos, where shared worship spaces foster interfaith dialogue.: 853–879 Movements like Eckankar and the Grail Movement, each with thousands of adherents, emphasise spiritual enlightenment and appeal to educated youth in urban centres. These groups, though niche, enrich Nigeria's pluralistic urban religious landscape, often incorporating indigenous spiritual elements.: 53–55

Atheism and irreligion Atheism and irreligion, though uncommon in Nigeria, are increasing among urban youth, with approximately 1% of the population—about 2 million people—identifying as non-religious. Non-believers face intense social stigma, often perceived as immoral in rural Muslim and Christian communities where religion is deeply ingrained. In northern states, atheists risk violence and prosecution under sharia-based blasphemy laws, exemplified by the 2020 arrest of Mubarak Bala for social media posts critical of Islam. Online platforms and social media communities like Nigerian Atheists, and events in Lagos provide safe spaces for non-believers to connect. Despite these challenges, irreligion highlights growing pluralism in Nigeria's urban centres.

Inter-religious dynamics Nigeria's religious diversity, including Islam, Christianity, and traditional belief systems, has profoundly shaped its national identity through both cooperation and conflict, influencing socio-political landscapes.

Historical tensions Religious conflicts before 2000, often intertwined with ethnic and political divides, include the 1987 Kafanchan riots, triggered by Christian-Muslim disputes, and the 1990s Jos crises over indigene-settler rights. These clashes, frequently in the Middle Belt, stemmed from competition for resources, political power, and religious dominance, with events like the 1994 Zango Kataf conflict highlighting ethnic-religious fault lines.: 75–80 The introduction of Sharia law in northern states like Zamfara in 1999 escalated tensions, with Christians fearing marginalisation, leading to protests and violence in Kaduna in 2000.

Contemporary conflicts Since 2000, religious violence has intensified, particularly in northern Nigeria. The Islamist group Boko Haram, founded in 2002, has waged a violent insurgency to impose strict Sharia, targeting Christians, moderate Muslims, and government institutions. Notable attacks include the 2011 Christmas Day bombings of churches in Jos and the 2014 Chibok schoolgirls kidnapping, which drew global attention. Boko Haram's actions have killed over 50,000 and displaced millions, deepening Christian-Muslim mistrust. Herder-farmer conflicts, primarily in the Middle Belt, also have religious undertones, pitting mostly Muslim Fulani herders against predominantly Christian farmers. Disputes over land and grazing rights have led to thousands of deaths since 2010, with attacks in Plateau and Benue states often framed as religious violence. A 2022 Freedom House report noted that these clashes, while rooted in resource competition, are exacerbated by religious rhetoric, complicating peace efforts.

Efforts at coexistence Despite tensions, inter-religious cooperation exists, particularly in urban areas. Grassroots initiatives, such as joint Christian-Muslim community projects in Kaduna, foster mutual understanding. The Nigeria Inter-Religious Council (NIREC), co-chaired by the Sultan of Sokoto and the President of the Christian Association of Nigeria, promotes dialogue and conflict resolution. A 2024 institutional study published by the Consortium of Universities in Kwara State (KU8+) and the University of Ilorin examined the advocacy of Professor Is-haq Olanrewaju Oloyede in promoting interfaith harmony. The report highlighted his efforts to implement interreligious cooperation through his leadership roles at the Nigeria Inter-Religious Council (NIREC), the Nigerian Supreme Council for Islamic Affairs (NSCIA), and the Joint Admission and Matriculation Board (JAMB). The authors describe Oloyede as having "put his concepts and ideologies into a pragmatic mechanism in everything he is saddled with." The symbolic placement of the Abuja National Mosque and National Church opposite each other in the capital underscores Nigeria's commitment to pluralism. Syncretic movements like Chrislam in Lagos further blend Christian and Islamic practices, promoting tolerance.: 123–125

Religion and politics Religion profoundly influences Nigerian politics, shaping voter behaviour, governance, and policy, often along regional and ethnic lines.

Political influence Religious identity often dictates political alignments. Northern Muslim voters typically support parties with Islamic leanings, while southern Christians back candidates advocating secular or Christian-friendly policies. The 1999 adoption of Sharia in 12 northern states, led by Zamfara, sparked debates over Nigeria's secular constitution, with Christians arguing it violated religious freedom. Political candidates frequently leverage religious rhetoric, with Muslim and Christian leaders endorsing candidates to sway congregations.

Secularism and challenges Nigeria's 1999 Constitution guarantees freedom of religion and declares the state secular, but implementation is uneven. In northern states, Sharia courts operate alongside secular ones, handling civil matters for Muslims, which some Christians view as discriminatory. Religious lobbying, such as the Christian Association of Nigeria's push for pilgrimage subsidies, mirrors Muslim demands for Hajj support, highlighting how religious groups influence public policy.

Electoral dynamics Elections often reflect religious divides. The 2023 presidential election saw debates over a Muslim-Muslim ticket by the All Progressives Congress, raising concerns among Christians about representation. Historical power-sharing agreements, like alternating the presidency between northern Muslims and southern Christians, aim to balance religious and regional interests, though these are informal and often contested.

Cultural and social impact Religion permeates Nigerian culture, influencing art, music, education, and social norms, while shaping both unity and division.: 200–205

Art and music Religion profoundly shapes Nigerian art and music, reflecting the country's diverse spiritual traditions—indigenous beliefs, Islam, and Christianity—and their interplay with ethnic and regional identities. These art forms serve as expressions of faith, cultural preservation, and social commentary, influencing both sacred and secular spheres.: 150–155 : 200–205

Traditional art and music Indigenous religious practices, rooted in ethnic traditions, manifest vividly in Nigerian art and music. Among the Yoruba, Ifá divination inspires intricate carvings and chants that invoke deities like Orunmila, preserving spiritual narratives through oral and visual media.: 15–20 Igbo masquerade dances, such as those during the Mmanwu festival, blend music, costume, and performance to honour ancestors and spirits, with vibrant masks symbolising divine connections. In northern Nigeria, Hausa griots perform oral poetry and music tied to traditional beliefs, often integrated with Islamic influences post-19th-century Sokoto Caliphate.: 53–55 These practices, whilst declining due to urbanisation, remain culturally significant, especially in rural festivals.

Islamic influences Islamic art and music in Nigeria, particularly in the north, emphasise non-figurative expression due to religious prohibitions on idolatry. Calligraphy, featuring Arabic script, adorns mosques in cities like Kano and Sokoto, with geometric patterns symbolising divine order.: 15–20 Musical traditions include nasheed, devotional songs praising Allah, performed by Hausa and Fulani artists during religious festivals like Eid al-Fitr. Sufi orders, such as the Tijaniyya, incorporate rhythmic chants and drumming in dhikr ceremonies, blending local rhythms with Islamic spirituality.: 180–185 These forms, whilst regionally prominent, face criticism from some orthodox Muslims who view music as un-Islamic, highlighting intra-religious tensions.

Christian influences Christianity, dominant in southern Nigeria, has spurred a vibrant gospel music scene that resonates nationally. Artists like Sinach and Frank Edwards blend African rhythms with Western gospel, filling stadia and shaping popular culture. Pentecostal choirs, backed by megachurches like the Redeemed Christian Church of God, perform at large-scale events, with songs addressing themes of salvation and prosperity. Christian art includes church murals and sculptures, particularly in Igbo and Efik communities, depicting biblical scenes with local motifs, such as Jesus in traditional attire.: 53–55 The rise of gospel music since the 1980s reflects Nigeria's Pentecostal boom, with artists gaining international acclaim.

Nollywood and media Nollywood, Nigeria's prolific film industry, is a vibrant medium for exploring religious themes, reflecting the country's diverse spiritual landscape and societal values. Films such as Living in Bondage (1992) depict spiritual conflicts between Christianity and indigenous beliefs, whilst others explore Muslim-Christian tensions or interfaith harmony, resonating with Nigeria's pluralistic populace. These narratives often emphasise redemption, divine intervention, or moral lessons, embedding religious motifs in popular culture. Gospel and nasheed music feature prominently in film soundtracks, amplifying their cultural and spiritual reach, particularly in urban centres like Lagos. Nollywood's portrayal of religion also engages with social issues, such as gender roles and communal harmony, often framing solutions through a spiritual lens. Despite its commercial focus, Nollywood faces criticism for occasionally oversimplifying complex religious dynamics, yet its global influence continues to grow, shaping perceptions of Nigerian spirituality worldwide.

Future trends Nigeria's religious landscape is evolving, driven by demographic shifts, urbanisation, and global influences.

Demographic projections Pew Research projects Nigeria's Muslim population growing to 55% by 2050, driven by higher fertility rates (7.2 vs. 4.5 for Christians), though Christians will remain significant at ~43%. Traditional beliefs may decline to under 1%, but cultural practices will persist in festivals and rites. Urbanisation will boost minority faiths like Baháʼí and Hinduism in cities.: 123–125

Emerging challenges Rising secularism among urban youth, with 1–2% identifying as non-religious, may challenge religious dominance, though social stigma limits growth. Climate change and resource scarcity could exacerbate herder-farmer conflicts, with religious undertones, threatening stability. Boko Haram's insurgency, though weakened, remains a security concern, potentially fueling interfaith distrust.

See also Culture of Nigeria Islam in Nigeria Christianity in Nigeria Traditional African religions Superstition in Nigeria Sharia in Nigeria Boko Haram Nigerian Constitution

References External links Pew Research Center: Islam and Christianity in Sub-Saharan Africa Afrobarometer: Nigeria Surveys Nigeria Inter-Religious Council UNESCO: Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove